I made use of FreeRTOS’ timer functionality in the most recent post in this series, but I didn’t go into detail because the post was focused on other features. It’s time to address that deficiency. Today I’m talking about timers.

I made use of FreeRTOS’ timer functionality in the most recent post in this series, but I didn’t go into detail because the post was focused on other features. It’s time to address that deficiency. Today I’m talking about timers.

One of the reasons why an embedded application developer might choose to build their code on top of a real-time operating system like FreeRTOS is to emphasise the event-driven nature of the application. For “events” read data coming in on a serial link or from an I²C peripheral, or a signal to a GPIO from a sensor that a certain threshold has been exceeded. These events are typically announced by interrupting whatever job the host microcontroller is engaged upon, so interrupts are what I’ve chosen to examine next in my exploration of FreeRTOS on the Raspberry Pi RP2040 chip.

Continue readingFreeRTOS scheduling is hard in as much at can be difficult to decide how to configure it. I wanted to try and figure out the options.

The popular real-time operating system provides the configUSE_TIME_SLICING and configUSE_PREEMPTION as settings values. You can add them to your FreeRTOSConfig.h file Tasks themselves can be assigned priority values, and there are API calls to allows tasks to sleep, to yield up the CPU, and be suspended and subsequently resumed.

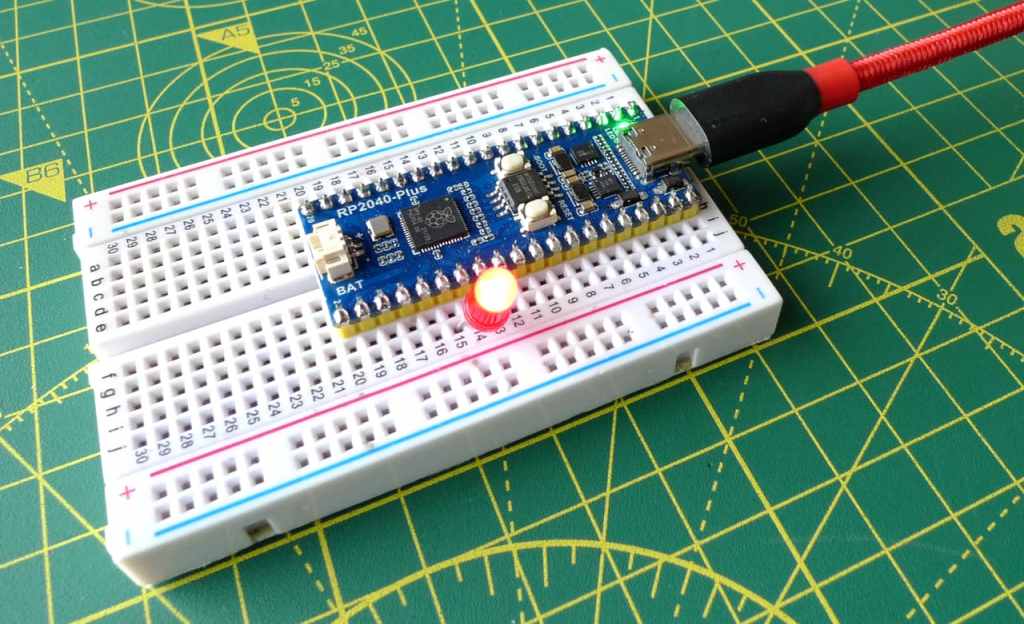

While documenting Twilio’s in-development Microvisor IoT platform, I’ve been working with FreeRTOS, the Amazon-owned open source real-time operating system for embedded systems. Does FreeRTOS work with the Raspberry Pi Pico’s RP2040 chip? I wondered. It turns out that it can, and this is how you set up a very basic FreeRTOS project which also serves as a demo.

My Raspberry Pi Pico-based Motorola 6809 emulator uses the RP2040’s built-in serial-over-USB functionality to receive machine code sent from a host computer. The 6809 and its support code is written in C, but can you make use of the same process under Python? Yes, you can, and here’s an easy way to do it.

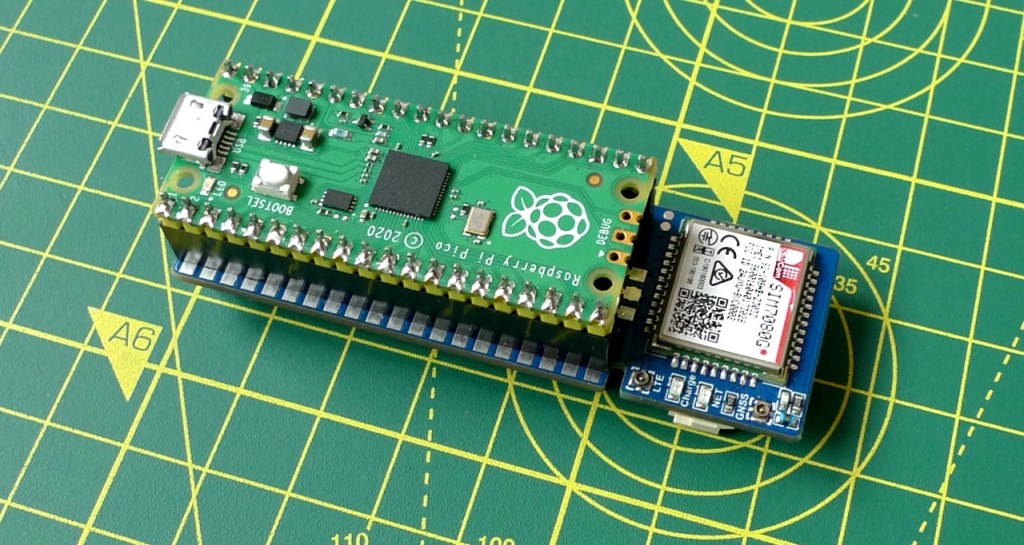

Continue readingLast Summer, I explored using the Raspberry Pi Pico as the basis of a cellular IoT device. That done, I wanted to try out WiFi connectivity. To do so, I ordered a Pimoroni PicoWireless.

Continue readingI recently upgraded my ageing iPad to a new iPad Pro 11. This has a USB C port, and I immediately wondered if I could use this to connect a USB C equipped Raspberry Pi RP2040-based device like the Adafruit Feather RP2040, and do development on the iPad rather than a Mac. The answer is a cautious ‘yes’, provided you can work to a very specific limitation: your RP2040-side application environment has to be CircuitPython.

Continue readingA wee while back I ordered a Pimoroni PicoSystem to try out. It’s a small handheld games console based on the Raspberry Pi RP2040 microcontroller, and it sports both classic joypad controls and a 240 x 240 16-bit colour display. I gave my first impressions in an earlier post. Here’s what I think after spending some time porting my Raspberry Pi Pico version of the 1980s 3D shooter Phantom Slayer to the unit.

Continue readingI’ve had my eye on the PicoSystem, the Raspberry Pi RP2040-based games console platform, for some time. It surfaced back in the Spring and was long marked “coming soon”. But now it’s here, mine showed up yesterday while I was at work, and this morning I’ve been messing about with it.

Continue readingIn part one, I described an IoT demo setup based on the Raspberry Pi Pico and the Waveshare Pico SIM7080G Cat-M1/NB-IoT cellular add-on board, and wrote about some of the design goals. Now it’s time to implement that design with some C++ code: a host application, drivers for the modem, the HT16K3-based display and the MCP9808 temperature sensor, and some third-party libraries to decode incoming commands formatted as JSON and encoded in base64 for easy SMS transmission.