This short post is in praise of analogue technology, specifically my Mitutoyo vernier callipers, which I picked up a couple of years ago for no good reason beyond fond memories of time spent in Physics labs during my undergraduate days.

Even so it has had, and continues to get, a fair bit of use.

Best of all, it requires no power source and needs no consumables. Indeed it expects nothing extra beyond its own good self. Of stainless steel construction, it will last me out and will never cost me a penny more to operate than I paid for it.

You have to learn how to read it, of course, but once you do — and it’s not hard — you will surely be impressed with the clever simplicity of it. It provides an accurate reading of up to half a millimetre, which is sufficiently fine for my needs.

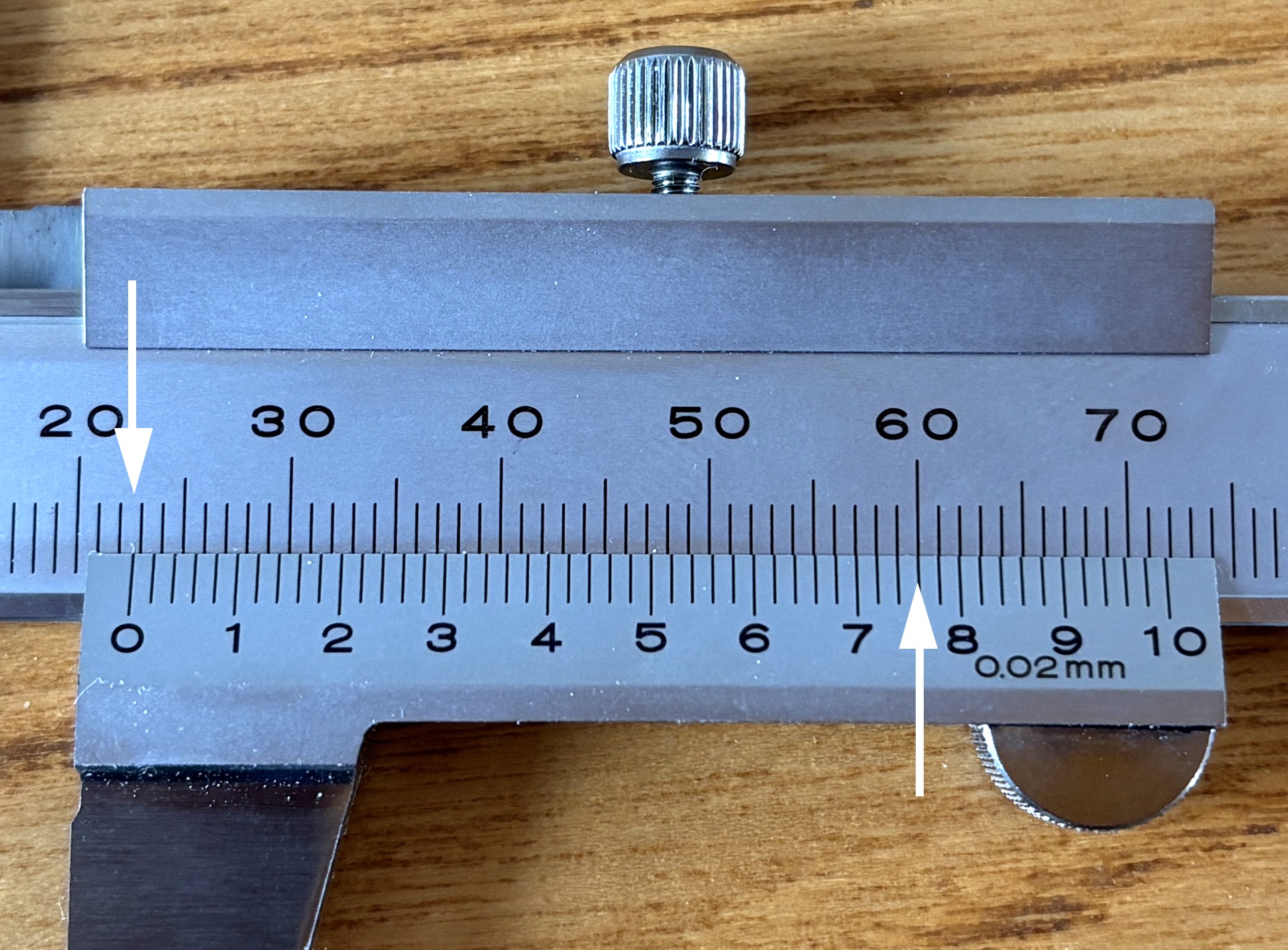

So how does it work? It consists of a millimetre scale and, alongside it, a second scale that’s in units of 0.02mm. To take a reading, you note the value of the millimetre scale mark immediately to the left of the second scale’s zero mark as your exponent (the bit before the decimal point, in floating-point terminology) and scan along the second scale to find where the two scales coincide. That gives you the fractional part of your reading.

Here’s an example. As you can see from the picture above, the top scale value to the left of the lower zero is 22. Working along the lower scale, you can see that the marks align at 7.6. So the distance between the pincers is 22.76mm.

Easy and unforgettable.

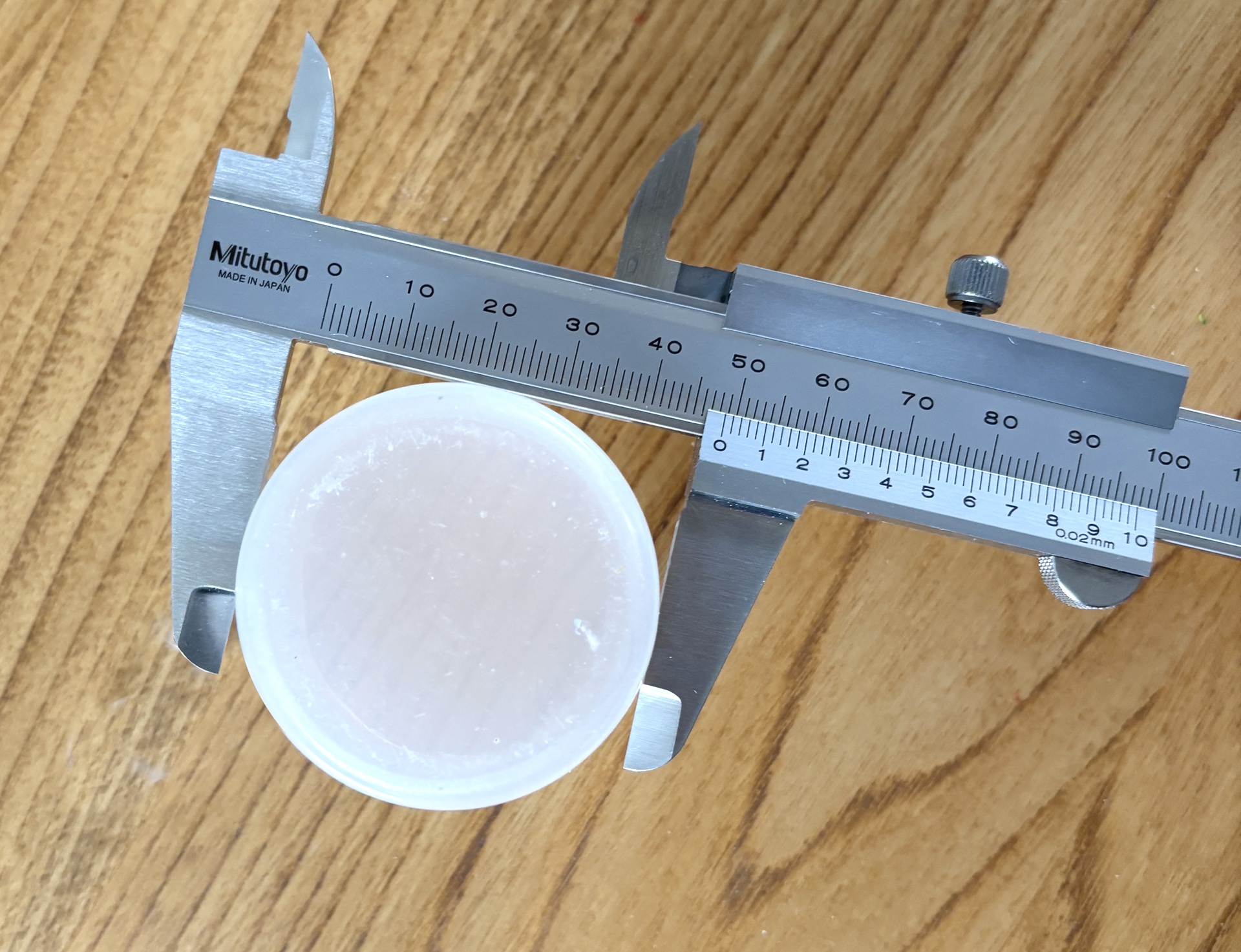

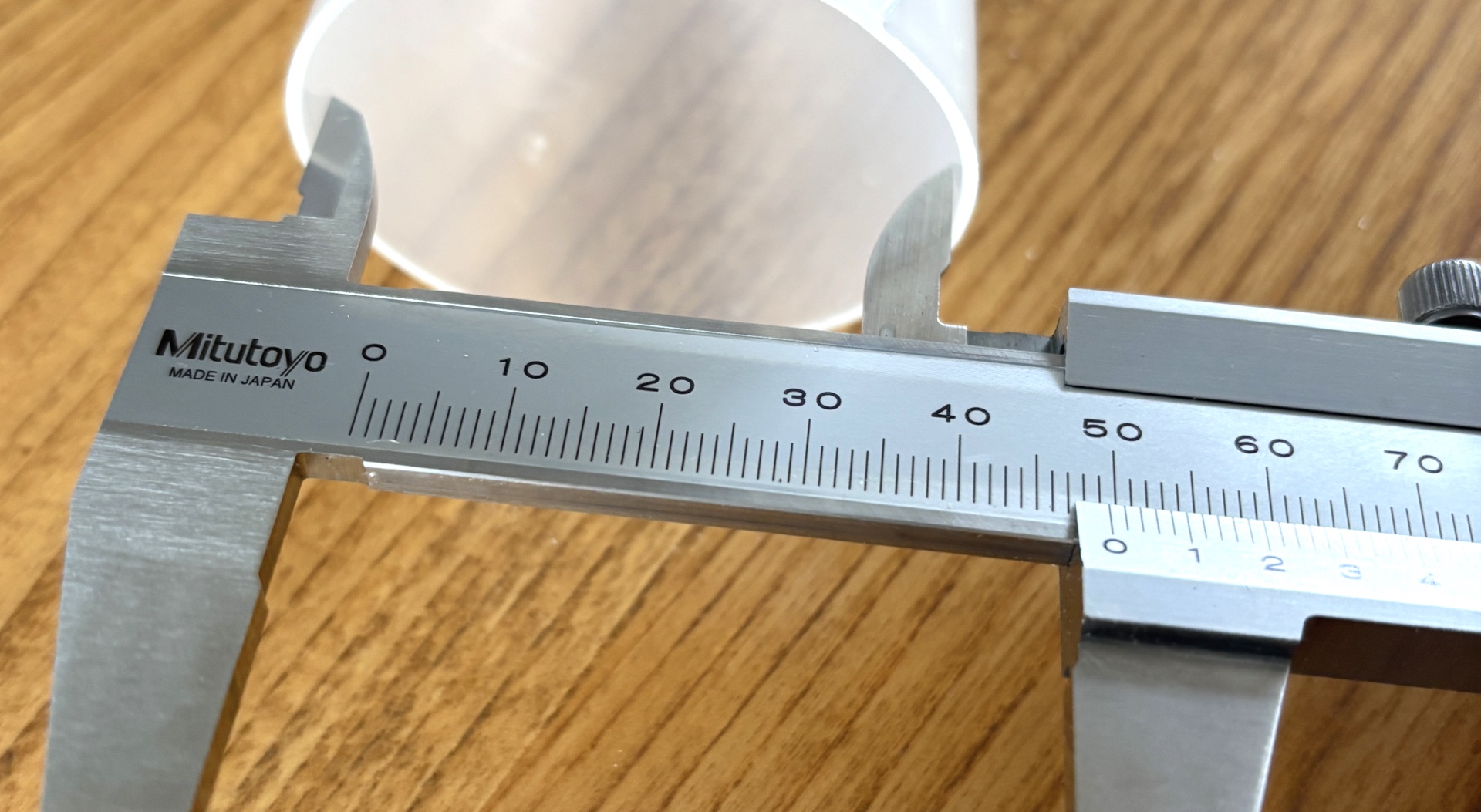

The main pincers are used to measure the separation of the outer edges of an object, but there are also two that are used to measure inner distances. So you can check the both the external and the internal diameters of pipes, for example. There’s also a screw on the top that allows you to control how smoothly the two scales move alongside each other and, if required, to lock the pincers in place should you need, say, to check that a number of items all match a measurement pre-set on the calipers.

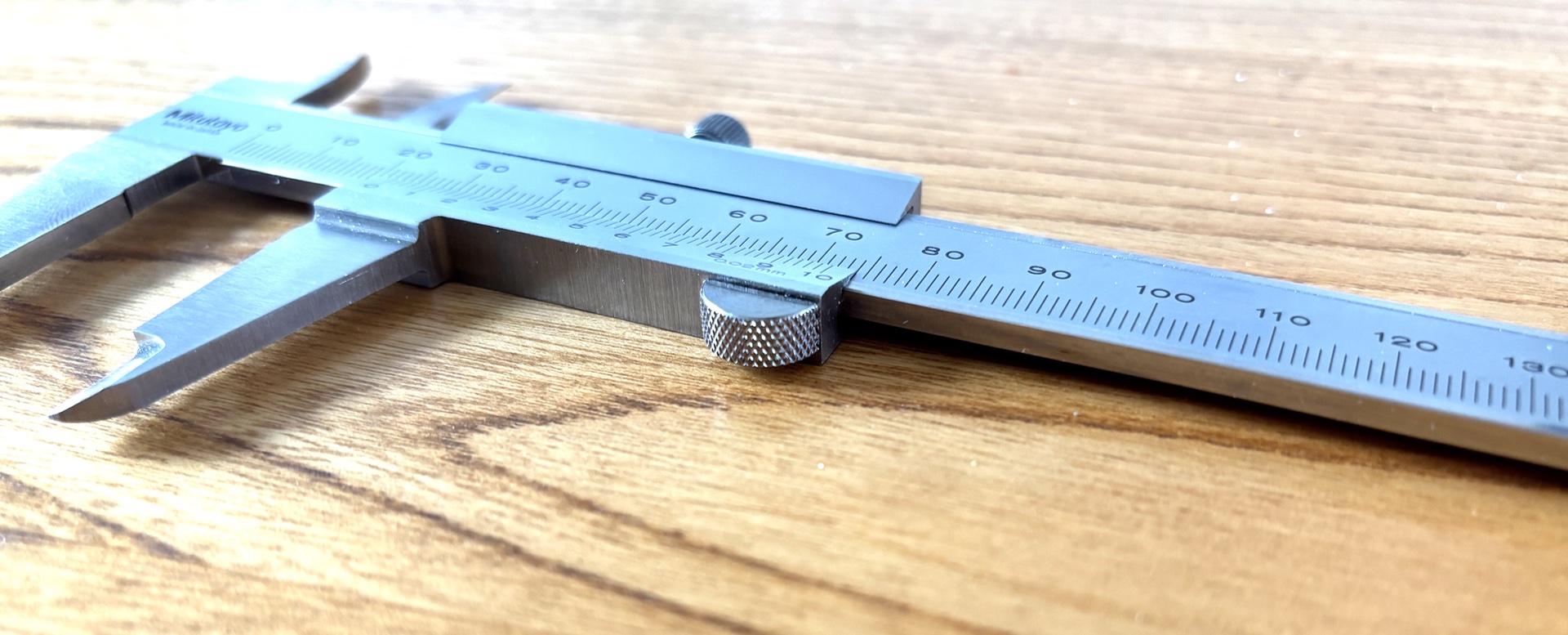

I happen to like the blob on the lower side of the lower scale which allows you to finely slide it back and forth with your thumb. But that’s a nice to have rather than an essential.

There’s a third means of measuring. The pointy bit at the end can be used to gauge depths. Moving the pincers extends the pin.

Discovery of the method of aligning two slightly different scales alongside each other in order to determine sub-scale values goes to Seventeenth Century French mathematician Pierre Vernier. You can read his bio at Wikipedia.

And that’s it really. Just a precision-constructed scientific instrument that is naturally tuned to the way the real world values flow from one to another in a way the digital world of discreet values with nothing in between is not. Sure, digital can emulate the analogue, primarily through floating-point values, but there will always be a level of clunkiness about it, as anyone who has set a float to 1.0 and read back 1.0000001 will appreciate. There is a loss of precision and an uncertainty that have to be worked around. The Vernier callipers don’t have to fudge.

Unless, of course, you buy one with a digital readout, which completely misses the point, I think.