The Uniform Type Identifier — UTI for short — is an interesting means to map files to the type of data they contain. macOS uses UTIs to work out what kinds of file an application can open to view or edit. My Preview… apps rely on UTIs to indicate their interest in certain file types. The system uses that information to pass files to my application extensions when a user previews a file using QuickLook. Generally, they’re hidden from users.

There’s a flaw in the system, however. A UTI might indicate the content a file might be expected to contain, but how does the system connect a file to a UTI? By using its file extension. But while UTIs are unique, file extensions are not, and this is where the trouble begins.

A case in point: TypeScript files typically have the ts file extension. Unfortunately, so do MPEG-4 transport stream files. Given an arbitrary file whose name ends in .ts, what does it contain? TypeScript source code or video data? And so which QuickLook previewer does Finder direct the file to? Finder could expensively look inside the file to check the contents, but instead it uses the UTIs it knows about, mapping that ts to one or more of them.

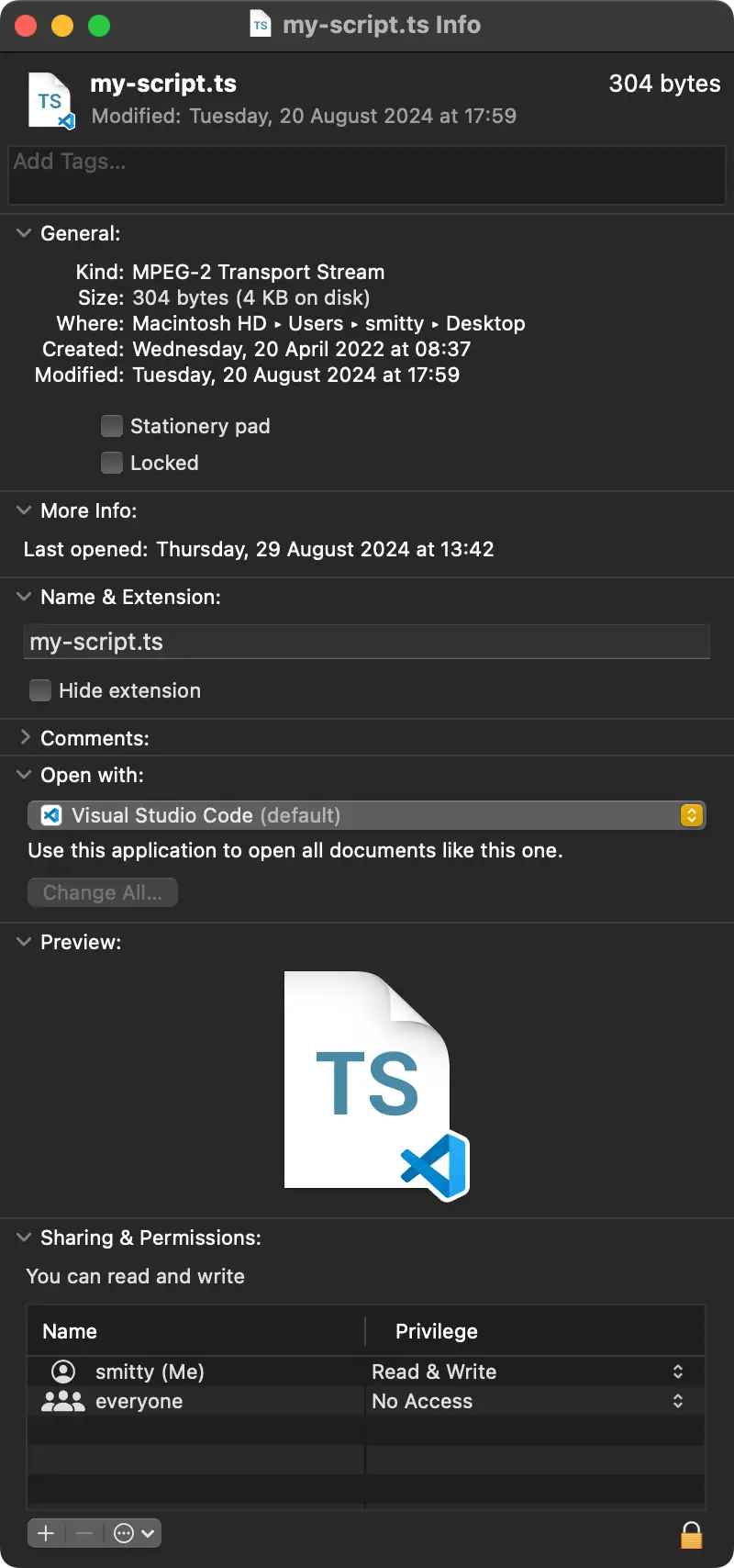

Unfortunately. when it looks up the ts extension in its database, macOS finds the UTI public.mpeg-2-transport-stream first, ahead of com.microsoft.typescript so directs the file to its MPEG viewer rather than, in this case, PreviewCode. Even though I have no .ts video files on my Mac there are quite a few .ts TypeScript source-code files. But PreviewCode never gets called. Finder’s Get Info command allows you to target files to a specific app for opening, but has no effect on app extensions providing QuickLook previews and Finder icon thumbnails.

Of course, part of the problem is users’ unwillingness to embrace and adopt file extensions longer than three or four characters. macOS and Linux have long been able to handle any number of filename characters past the period. Heck, so has Windows. I’m pretty sure it has done so a lot longer than TypeScript has been around.

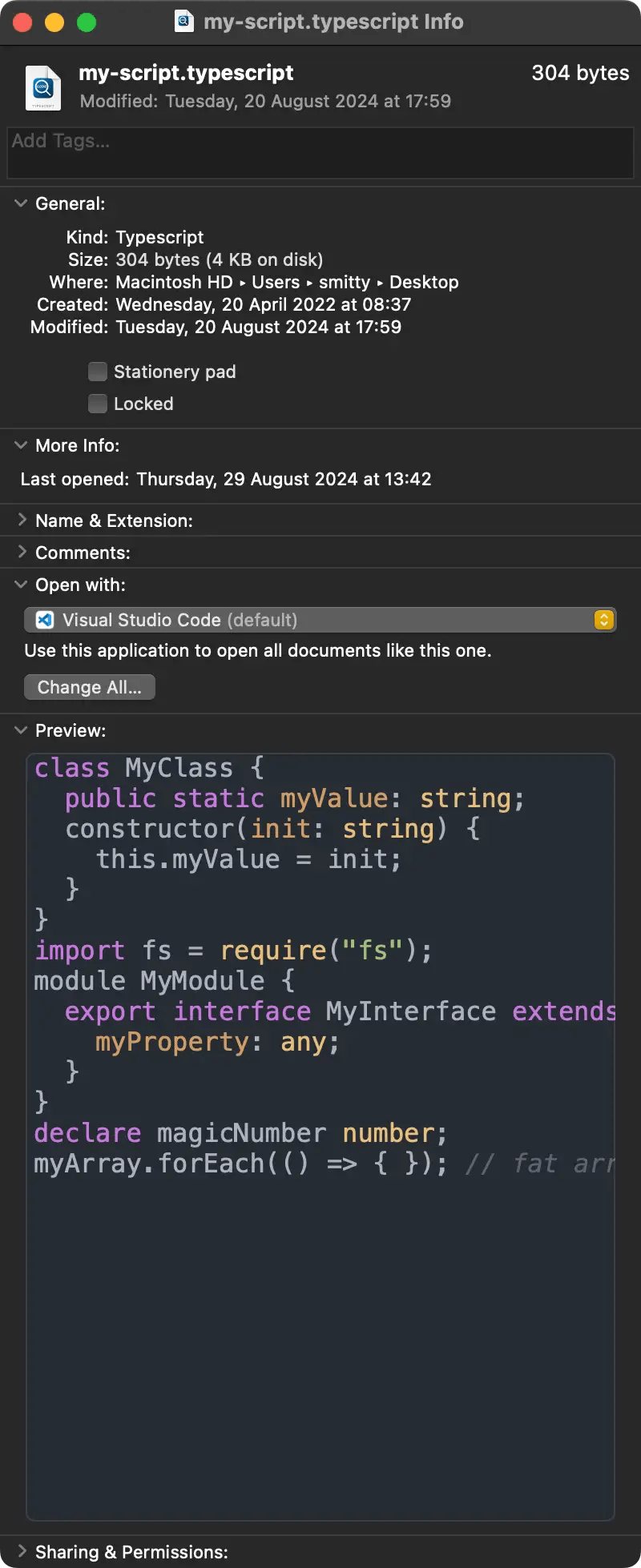

So why is ts the standard file extension for TypeScript files and not the obvious typescript? You can use that extension — and PreviewCode will receive the file to generate a highlighted preview from it — but of course almost nobody does! Yet unlike ts, typescript can be uniquely associated with TypeScript source-code files.

I suspect Apple’s engineers anticipated this when they devised the UTI back in 2006. Had longer extensions become commonplace, clashes of the ts kind would have been virtually eliminated. Alas history has proved those engineers wrong. Applications and users stubbornly refuse to adopt long extensions. We’ve just become too accustomed to txt, png, jpeg, mp3, etc. So virtually every TypeScript coder expects to work with files ending in .ts and nothing else.

So how do we deal with the situation as it is, not how Apple engineers once wanted it to be? “Having defined a problem, the first step towards a solution is the acquisition of data.” To that end, I wrote utitool, a command line utility to reveal the UTI linked to any given file. It was released a few years back and has proved a very useful diagnostic assistant. especially when providing customer service for Preview… apps. I’ve since updated it to add UTI lookups for not only files but also specific file extensions and, if you have a UTI, to learn what applications are linked to it.

This week I posted a further utitool upgrade, this time to add system record exploration. macOS’ Launch Services maintains a registry of applications (bundles, really) and the UTIs they export (define) and import (support without defining) along with ancillary information such as associated file extensions, MIME types and the URL of the website at which the content format is defined. The data this registry contains can be read out in macOS’ Terminal app, but in a less-than-optimal, all-or-nothing form. The saved output runs to 20-odd megabytes on my system. So I wrote some code to get the output then extract useful UTI and app info.

Parsing the data isn’t straightforward because the output is in human-readable form, but once done, we have information that can be presented in (friendlier) human-readable form or output as JSON. The latter is presented via STDOUT so it can be piped into other analysis tools, such as jq. You should note that UTIs contain periods/full stops. For jq these are reserved characters, so UTIs need to be quoted. For example:

utitool --list --json | jq '."com.adobe.pdf".extensions'Of course, Apple uses UTIs in many roles other than file-content indication. For example, It identifies all of its devices using UTIs. Likewise its array of macOS UI icons. All of these are defined in macOS’ CoreTypes bundle, which also records most if not all public content-type UTIs. This necessitated some hackery to ignore the unwanted UTIs as there’s no consistent flag for UTI types.

Even without these, CoreTypes defines many, many UTIs.

Using the tool reveals, for instance, that ts is registered for TypeScript files, but the MPEG-4 Transport Stream UTI comes first on the list, as the picture at the top of this article shows. Clearly, macOS doesn’t look beyond that first entry when deciding what kind of content a file contains and therefore what QuickLook previewer to open for it — even if, say, you have told Finder to open all .ts files in Visual Studio Code.

Work on finding a way around this issue continues. In the meantime, you can download utitool 1.2.0 from my website, or build it from source after cloning the source code, to pursue your own investigation of macOS’ UTIs.