I’m not especially a fan of the ‘quantified self’, the notion that I should continuously record massive amounts of data about my daily life and physiological state. But I am keen on Bluetooth LE communications, and this reason, not the former, is why I acquired a Colmi R02 “smart ring” from the PRC.

And all for a mere £6.24 including postage and packing. Barg!

The ring contains a tiny microcontroller and BLE radio, plus an accelerometer for step counting, a blood oxygen reader and a heartbeat sensor. It’s powered by a battery recharged using a tiny magnetic jack that you plug into any USB adaptor. Wee it may be, but the 17mAh battery will give you around five days’ usage on a full charge. From its size, the MCU looks like it’s the BlueMicro RF03, but the precise type is not stated in the ring’s specs.

I heard about the R02 on Hackaday a little while ago. The story pointed out that the ring performs all its communications over BLE, including firmware updates, and that that BLE link is not encrypted — with all the risks that that implies. The upshot for me: although there are official free iOS and Android apps to pull data off the ring, it’s possible to write my own code to get the data myself and wrangle it as I see fit.

Hackaday pointed out a Python-based CLI project, which I tried but ran into some issues on macOS. No disrespect intended: the project’s fairly recent and it’s a work in progress. But I felt that falling back on other folks’ work was not much different from just installing the stock app. I’d bought the ring to play with more than as an activity tracker, so I decided to get down and write my own client.

Being a fan of Tiny Go, a Go toolchain for embedded applications, and knowing it has a BLE stack built in, I opted to use it as the basis for my own smart ring command line client. I hadn’t, at this point, ever used Tiny Go’s BLE code, so this was an excellent opportunity to learn how it works.

Using Punch Through’s LightBlue BLE scanner app, I could see the ring’s name and BLE GATT services, their UUIDs and those of the services’ characteristics. Apart from the standard Device Information service, the ring provides a mechanism to write packets to it that request data, such as battery level and charging status, and then asynchronously ping the response back as a notification. I’m reliably informed it’s a lot like Nordic Semiconductor’s UART-over-BLE service, right down to the same characteristic UUIDs.

There’s a third service, also with a ‘write request’ characteristic and a notification characteristic to provide the response, but I haven’t figured out what that one does yet. That’s for when the basic ring functionality is done.

Fortunately, there’s a growing pool of reverse-engineered information on the Interweb, so many such gaps have (or probably will shortly be) filled.

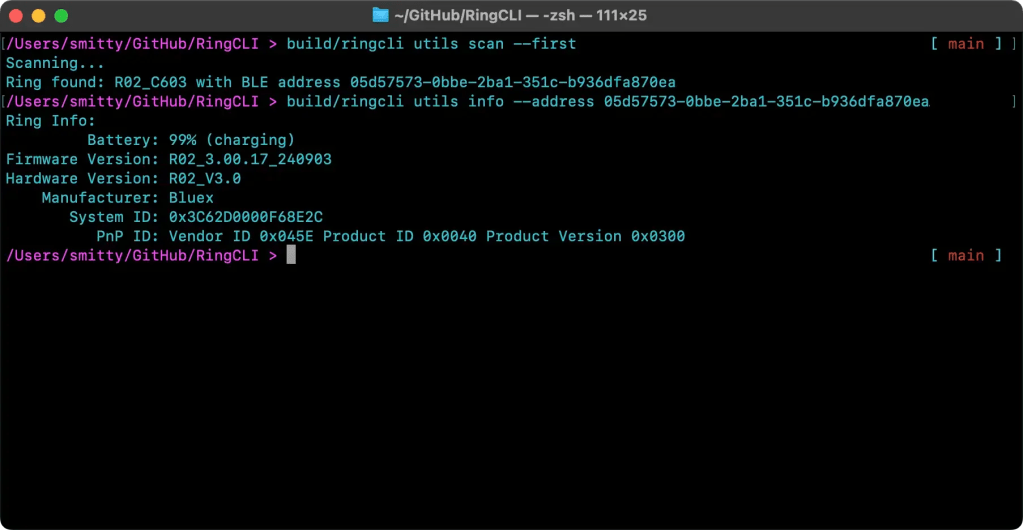

The first step in building my own client was to check out the Tiny Go BLE stack by setting up a scan to locate the R02 and get its name and address. That done, the next step was to access the BLE-standard Device Information service. Straightforward, that, but it proved that language and tooling could be used as intended.

Battery status isn’t part of the Device Info, so that was the next task, and it took me to the UART. Thanks to the work of @puxtril and @tahnok, I knew the format of the data to write to the UART’s input (TX for me) characteristic, which I did after subscribing to notifications issued on the output (RX). Notifications are issued only while client and ring are connected, but since other responses might come through the same RX, it’s prudent to check that the responses match your requests as they come through.

It actually works surprisingly well, and Tiny Go’s BLE stack supports this kind of task well. You have to watch that the code doesn’t complete before the callback into which the notification is passed is triggered, but that’s easy to do. Don’t do what I did and mis-key the RX characteristic by a single digit, as it won’t work and your error will be tricky to spot!

Battery data is returned in a single packet. No so your step count: it’s not only included in a packet that also contains (usefully) distance travelled and calories burned, but the ring also issues multiple, historical data sets rather than a single, cumulative one.

Examining the packets received confirmed the key fields as outlined by @puxtril’s info site mentioned above (albeit taken from a different model of Colmi ring) but with some adjustment based on actual data. None of this is officially documented. You can see the expected date and sensors. Repeated viewing revealed what appear to be a packet count and the number of packets to be sent. Using that appearance as a working hypothesis I was able to use that to continue awaiting packets and processing received once until the last one has arrived and I can disconnect from the ring and output the accumulated totals.

Heart-rate data and blood oxygen counts (SpO2) work the same way, and the first of these I’ve implemented to give me up to a day’s worth of readings, from midnight to the time at which that data is retrieved. Like the activity data, one request packet yields multiple response packets: a couple of metadata packets and data for as many possible readings within a 24-hour period. How many depends on the reading interval set on the ring. Fortunately, there’s a command for setting that, and for reading it, so I get that value and use it to determine the interval in minutes between each data point embedded in the heart rate data packets.

Incidentally, that got me writing sub-commands to get and set the reading period, to set the ring’s internal clock (which you need to do the first time you use the ring), and to flash its indicator LED — handy if you’ve taken the ring off and can’t recall where you put it. The ring’s API call flashes the LED twice in quick succession, so I added an option to repeat this for a longer period to aid location. I’ve also implemented a means to persist the ring’s BLE address — obtain by running the CLI’s scan sub-command right at the start, so I don’t need to enter it with every command.

ringcli utils scan --first

You can find the code on GitHub here. It’s a work in progress, natch, with further CLI flags and options to be added, primarily to cache the downloaded data in a form for future use; I’m thinking .csv so it can be opened in any spreadsheet application. There’s also more ring data to expose, including blood oxygen log readings, and real-time data streams too, but it’s a start.

And one of the best bits is that although entirely developed on macOS, because it’s written in Go, the code also compiles and runs on my Linux machine too. It’s not (yet) as smooth in operation as it is under macOS, with connections failing if I don’t perform a scan first, even though the target device’s address is known, and a noticeable pause while the ring disconnects. These may be a quirk of bluez, the underlying library TinyGo’s BLE stack uses when it’s running under Linux. A temporary(?) fix is to install the blueman Bluetooth manager and mark the ring as trusted.